Why Germany's Greens Are on the Rise

After sixteen years of muddling through, the time is ripe for something new.

Germany’s Greens have for the first time in two years overtaken the ruling Christian Democrats in the polls. Two surveys in the last week gave them 28 percent support for the election in September against 21 to 27 percent for the center-right.

Those polls are still outliers, but the gap between the parties has been narrowing across surveys for months.

I suspect two factors are at play: leadership and a desire for change. I’ll take those in turn before laying out the different ways in which the Greens could take power.

Leadership

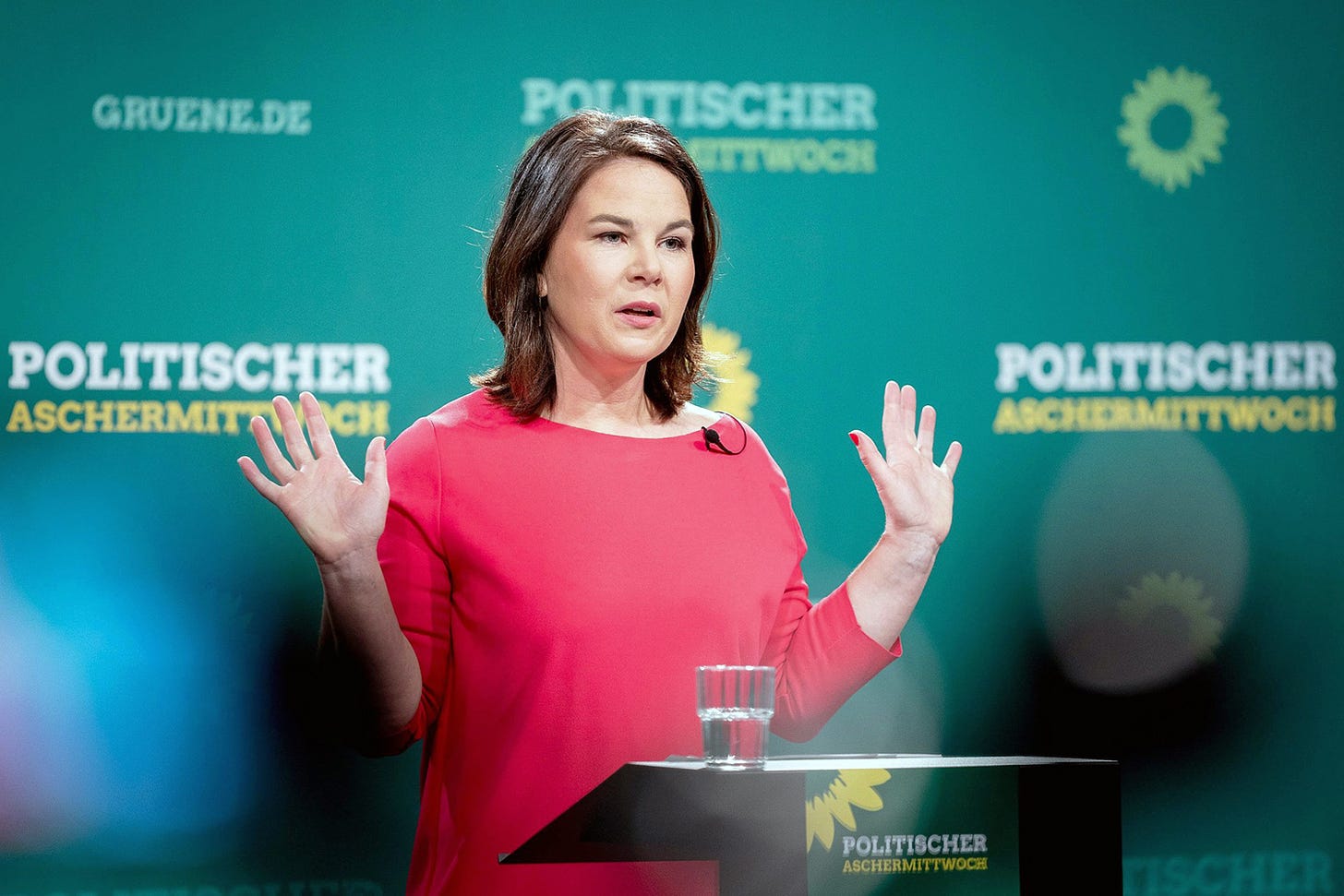

Der Spiegel puts it vividly: imagine the upcoming election debates. On the left, the 62 year-old former mayor of Hamburg and outgoing finance minister, Olaf Scholz, the candidate of the Social Democrats. On the right, the sixty year-old prime minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Armin Laschet, leader of the Christian Democrats. In the middle, a forty year-old mother of two who defies the stereotype of the well-intended but wide-eyed environmentalist.

Annalena Baerbock worked in international law and as parliamentary advisor before she was elected in her own right in 2013. She sat on committees for economic and family policy, and participated as a lawmaker in the 2015 Paris Climate Conference. A centrist in her own party, she has criticized the center parties for lacking ambition on climate and Europe and for not taking a harder line against Russia.

Something new

“The question,” argues Der Spiegel, is “whether the old wins out once again. Or whether the time is ripe for something new.”

I expect there will be a desire for change after sixteen years of muddling through. It’s why I argued Markus Söder, the prime minister of Bavaria, would make a better chancellor candidate for the right than Laschet: he represents a modernizing and more confident conservatism than the consensus-oriented Christian democracy of Laschet and the woman he hopes to succeed, Angela Merkel.

That is not to say Merkel’s centrism was wrong for the time, but it did leave issues unaddressed. Or, as Constanze Stelzenmüller puts it in an excellent profile of the outgoing chancellor in Foreign Affairs, “even her admirers concede that although she has been exquisitely adroit at riding out the currents of politics, she has been far too reluctant to shape them.”

Germany produces fewer university graduates per capita than its neighbors. Its 4G network is one of the worst in Europe. Investments in rail are falling short. Billions of euros spent on an Energiewende have at best evened out Merkel’s decision to phase out nuclear power, which increased reliance on coal and natural gas. Just before the pandemic, the World Economic Forum downgraded Germany from third to seventh place in its competitiveness index.

Merkel seldom answered questions about Germany’s identity or its place in Europe for fear of stirring old passions. As a result, many Germans felt changes, like a million refugees and bailouts of weaker euro states, happened to them. The popularity of the far-right Alternative for Germany, virtually unchanged at 11-12 percent since the last election and concentrated in the former East, is also her legacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has called conventional wisdoms into doubt, not in the least Germany’s reluctance to borrow and spend. The effects of climate change are starting to be felt in Europe, with summers getting hotter and flooding and storms becoming more frequent.

This doesn’t have to benefit left-wing parties per se, but I suspect it will benefit parties that (appear to) have a plan.

The Greens are proposing to invest €500 million in digitalization, infrastructure and emissions neutrality. They would phase out coal power by 2030, eight years ahead of Merkel’s schedule. They want to stop Nord Stream 2, the extension of the natural gas link between Germany and Russia under the Baltic Sea. They support a European minimum wage, a European Monetary Fund, a European Security Union for police and military cooperation, Europe-wide unemployment insurance and they reject integration at multiple speeds.

I don’t support every policy. I think a European minimum wage and European unemployment insurance are at best premature (even America doesn’t have the same policies in all fifty states), and I wish the Greens would back up their European Security Union with higher German defense spending. But I can’t accuse them of lacking ambition.

Nor that they’re unrealistic. The Greens’ emissions targets match those of the European Commission. Many of their proposals for EU reform match those of French president Emmanuel Macron. America and Eastern Europe also want Germany to pull out of Nord Stream 2. Nobody in foreign capitals will lose sleep over the prospect of the Greens coming to power in Berlin.

Possible coalitions

There are two ways that could happen, writes Jon Worth, a British-born blogger and member of the Berlin Green party:

A “Black-Green” coalition, similar to the one governing Austria. It would presumably double down on reducing emissions, take a softer line in Brussels and a harder line against Russia.

A “traffic light” coalition of Greens, Social Democrats and liberal Free Democrats. It works in Rhineland-Palatinate, but bridging left-right divides on issues like labor law, sustainability and taxes will be a challenge.

Many Christian Democrats would prefer a center-right coalition with the Free Democrats while the Greens would be more comfortable in a coalition with just the Social Democrats, but neither option is likely to have a majority in the next Bundestag.

An all-left coalition of Greens, Social Democrats and Die Linke could work domestically, but Worth doubts they would work out their differences on foreign policy. Die Linke is still anti-NATO and considers the EU a “neoliberal” project.

Another grand coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats may fall short, and neither party is keen to continue it anyway after seven years.