How Divided Government Works in France

Without a majority in the National Assembly, the president can still make foreign policy.

Emmanuel Macron may yet hold on to his majority in the National Assembly. His liberal alliance, renamed Ensemble (Together), won 350 out of 577 seats in 2017. Polls give it between 310 and 378 seats for the elections in June.

Based on their strong performance in last year’s regional elections, and given that Macron’s party has weak grassroots, I expected the center-right Republicans to do better. They still might. Republican voters, who on average are older than Macron’s, are more likely to turn out. But their disappointing performance in the presidential election — Valérie Pécresse got just 5 percent support — may also have demotivated conservatives.

The alliance of the far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon, left-wing Greens and center-left Socialists — who failed to unite in the presidential election and lost — has a third of French voters, but it could struggle in the decisive second voting rounds. Left-wing candidates would do best against a conservative or far-right opponent. Then they could count on the support of centrists. But where a left-wing candidate qualified against a Macronist, the latter would be preferable to Republicans.

The same dynamic works against the far-right Marine Le Pen. If a candidate of her National Rally makes the runoff, left to moderate-right voters tend to back their opponent.

The two-round voting system makes it difficult to predict the outcome altogether. Divided government, what the French call cohabitation, in which the presidency and National Assembly are held by different parties, is possible.

So how does that work in France?

It has happened three times

Although the president appoints the prime minister, the latter must also have the confidence of parliament. The president cannot dismiss the prime minister. The National Assembly can.

Since Charles de Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic, with its strong presidency and two-round voting system, in 1958, France has had three cohabitations. In all cases, the president accepted the leader of the largest party as prime minister.

Between 1986 and 1988, the conservative Jacques Chirac was prime minister for the Socialist president François Mitterrand.

When conservatives won the legislative elections in 1993, Chirac refused to serve under Mitterrand a second time. Édouard Balladur, the former finance minister, became prime minister for two years.

From 1997 to 2002, Chirac, by then president, had to accept the Socialist Lionel Jospin as prime minister.

Disruptive

None of the cohabitations were easy.

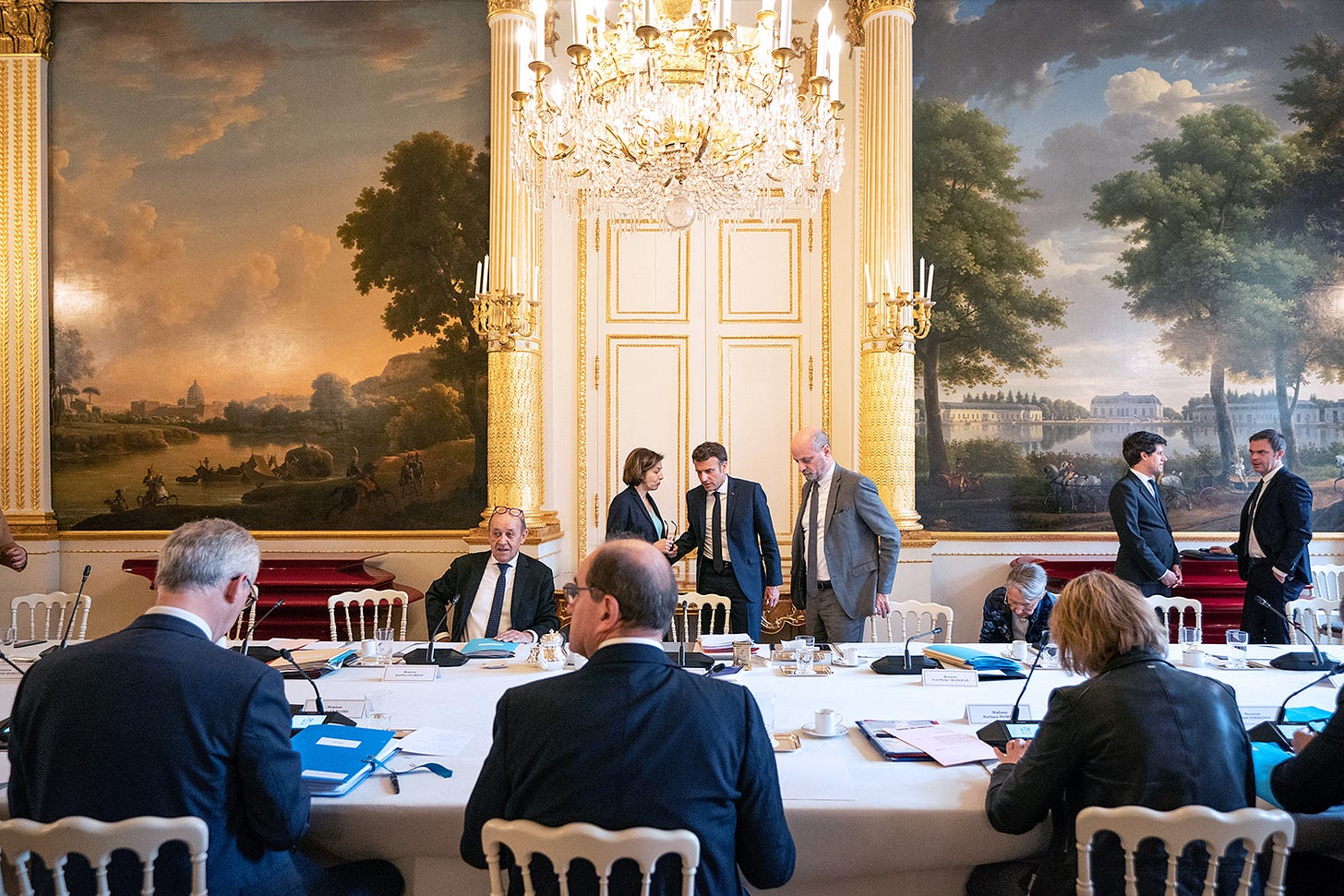

Without a loyalist in charge of his cabinet, the president is reduced to making foreign policy.

Technically, even responsibility for defense and foreign policy is shared between the president and council of ministers, but in all three cohabitations the prime minister focused on domestic affairs.

The first was the most disruptive. Chirac abolished the wealth tax, liberalized labor law and privatized some sixty state-owned enterprises. Mitterand, whose Socialist Party had nationalized those companies and industries in the first place, refused to give his approval. Chirac had to force him through a vote in parliament. Mitterrand relented, but still criticized Chirac’s decisions in televised speeches. Chirac wasn’t too flattering of Mitterrand either.

Balladur avoided confrontation. The Socialists had reintroduced the wealth tax after Chirac. Balladur kept it in place. But he continued the privatizations and reformed private-sector pensions, requiring the French to work longer.

Chirac was elected president in 1995 and made the mistake to dissolve parliament two years later. He hoped to win an outright majority, so he would no longer have to rely on small center-right parties. Instead the Socialists prevailed, and Chirac had to live with Jospin.

Jospin reduced the working week to 35 hours and rolled out universal health coverage, two initiatives Chirac opposed. The threat that Chirac might dissolve the legislature again, when the Socialists were polling so-so, kept Jospin from enacting more ambitious left-wing policies.

From seven to five years

The president has the power to dissolve the National Assembly once per year. Since Chirac’s dissolution in 1997 backfired, no president has risked triggering early elections.

During the third cohabitation, the conservatives and Socialists agreed presidential and legislative elections should ideally be held in the same year to reduce the risk of divided government. Presidential terms were shortened from seven to five years to match the mandate of the National Assembly.

Since then, legislative elections have been held within weeks of the presidential election and voters have always given new presidents a majority. Macron is the first president since Chirac to win a second term.