EU Can't Trust Britain to Keep Its Word

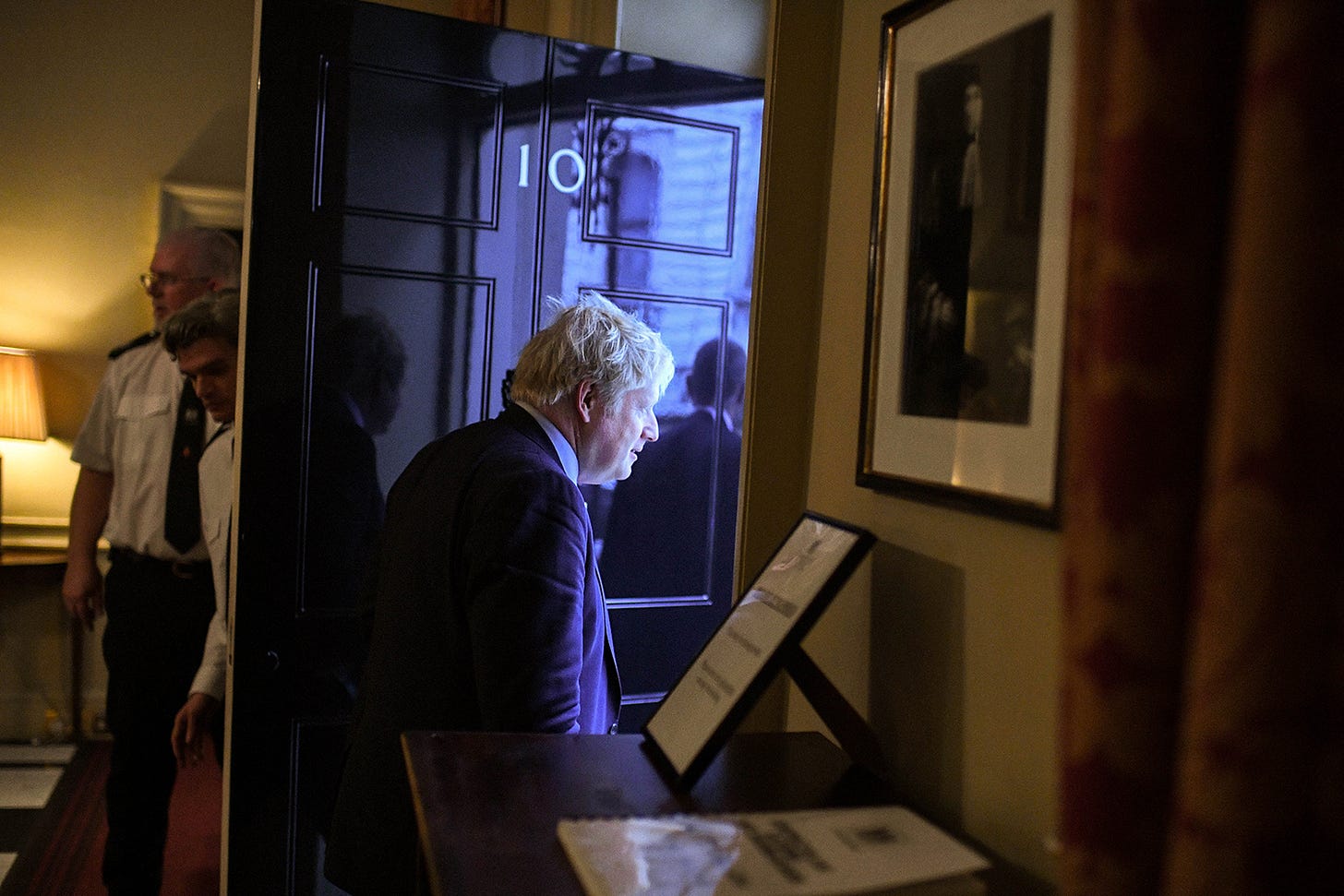

The British government reneges on its commitment to Northern Ireland — again.

How is the EU supposed to manage post-Brexit relations with a United Kingdom that won’t keep its word?

For the second time in six months, Britain has reneged on its Irish border commitments without consulting the EU or Ireland.

Northern Ireland is still in the European single market for goods under the EU-UK treaty. The rest of the United Kingdom is not, creating new regulatory barriers for British companies. They have struggled to cope. Supermarket shelves in Northern Ireland have gone empty. Parcels are stranded in Great Britain. The government of Boris Johnson has temporarily lifted the new rules to give businesses more time to adjust.

It’s not unreasonable to ask for a few more months of delay. But such a request should have been discussed in the Joint Partnership Council, which was created by the treaty on future EU-UK relations to manage precisely these situations. Instead, Britain acted unilaterally.

Not for the first time. In September, it weaseled out of its promise to respect EU regulations in Northern Ireland claiming it was breaching an earlier agreement with the EU in only a “specific and limited” way. As if that made a difference.

Irreconcilable

At the heart of the dispute are three irreconcilable demands.

Neither side wants border checks in Ulster. The open border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland has helped keep the peace between Catholics and Protestants in the region for twenty years.

The EU can’t accept an open external frontier. That would allow companies to import goods that don’t meet European standards and immigrants to enter European territory unseen.

But the solution the EU and the UK found in the Brexit negotiations — a customs border down the Irish Sea — is unpalatable to the British right, including many Protestant unionists in Northern Ireland. It cuts the United Kingdom in half.

Underscoring the sensitivity of the issue, three outlawed unionist paramilitary groups have announced they no longer feel bound by the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the decades-long insurgency in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

The announcement has no practical effect. Voters in Ireland and Northern Ireland approved the 1998 accord, and Northern Ireland’s political parties remain committed to the power-sharing institutions it created. But it’s a reminder that this is no mere political dispute.

Leaving the UK

On the other side of the sectarian divide, support for unification with Ireland is up. A poll conducted for The Sunday Times found that one in two Northern Irish voters would back a referendum on unification. Few polls have yet found a majority in favor of leaving the UK, but the trend is moving in that direction.

In Ireland, a majority has supported unification for years.

A Northern Irish majority voted to remain in the EU in 2016, but they were overruled by voters in England and Wales.

In Scotland, which voted against Brexit as well, support for independence is similarly on the rise.

Responsibility

I’ve argued here that Conservatives took a risk with the union when they called the Brexit referendum and neglected their responsibility to itin the subsequent divorce negotiations with the EU. Northern Irish and Scottish interests and wishes were given little weight. Warnings from Northern Irish and Scottish unionists, as well as economists, who argued Britain would be poorer outside the European market, were brushed aside.

Michael Gove, a former education secretary and leader of the official Brexit campaign, memorably told an interviewer, when asked to comment on the opinion of experts, “I think the people of this country have had enough of experts.” Ruth Davidson, an opponent of Brexit who led the Scottish Conservatives to their best election result in three decades, resigned.

Gove is still in government, and his party still refuses to take responsibility for the choices it has made — and imposed on Europe and the UK.

The EU has shown good will, offering the British more favorable trade terms than any other nation (which Johnson refused) and allowing a non-EU territory (Northern Ireland) to remain in its single market.

Still Johnson, Gove and their allies in Westminster and the British press blame the EU for a crisis they created. What is the EU supposed to do?